President Trump has issued an executive order pushing the United States to regain space leadership, aiming to return astronauts to the Moon and establish a sustained lunar outpost by 2030, while emphasizing commercial partnerships, cost-efficiency, and long-term American presence in space.

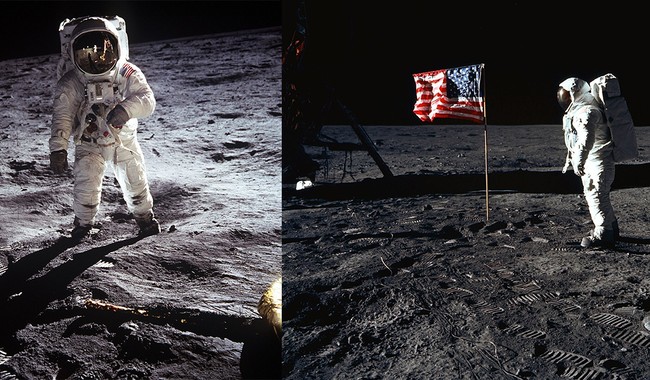

The U.S. remains the only nation to have sent humans to the Moon and brought them home, but that last occurred with Apollo 17 in December 1972. That gap has driven a sense of national urgency: the goal now is not just to visit, but to stay and build. The White House action is a clear signal that space policy will be about practical leadership and rapid progress.

The executive order lays out specific priorities for lunar effort and space dominance, and it aims to accelerate timelines that once seemed comfortably far off. Returning Americans to the Moon and setting up the beginnings of a permanent lunar outpost are central items, with commercial launch services singled out for support. This approach mixes government direction with private-sector energy to push past decades of relative inactivity.

Sec. 2. Policy. My Administration will focus its space policy on achieving the following priorities:

(a) Leading the world in space exploration and expanding human reach and American presence in space by:

(i) returning Americans to the Moon by 2028 through the Artemis Program, to assert American leadership in space, lay the foundations for lunar economic development, prepare for the journey to Mars, and inspire the next generation of American explorers;

(ii) establishing initial elements of a permanent lunar outpost by 2030 to ensure a sustained American presence in space and enable the next steps in Mars exploration; and

(iii) enhancing sustainability and cost-effectiveness of launch and exploration architectures, including enabling commercial launch services and prioritizing lunar exploration;

Putting people back on the Moon is technically achievable; we did it half a century ago and hardware, computing, and materials science have moved on since then. The bigger challenge is turning visits into habitation: long stays demand solutions for reduced gravity, radiation protection, life support, and sustainable logistics. Those problems are solvable, but they require concentrated planning, investment, and a willingness to accept the risks of bold timelines.

Lunar gravity—about one-sixth of Earth’s—presents real physiological concerns: extended exposure can erode muscle and bone in ways that complicate return to Earth. The Moon’s lack of atmosphere also means radiation shielding becomes essential for any long-term outpost. Addressing these issues will mean integrating robotic systems, improved habitat design, and medical countermeasures to protect crews over months or years.

Commercial space firms have changed the playing field, and the order recognizes that public-private partnerships will be crucial for cost-effective access and sustained operations. Private industry brings innovation and competitive pressure that can lower launch costs and speed development of essential technologies. When the goal shifts from short-term scientific sorties to economic development and habitation, commercial actors will likely be the ones to scale and sustain activity.

Beyond technical hurdles, there are strategic and economic reasons to press forward: lunar resources and capabilities could support broader American leadership in space and beyond. Establishing a foothold on the Moon can be a stepping stone to Mars and to tapping resources in near-Earth space and the asteroid belt. That potential transforms space from symbolic prestige into practical national advantage.

There will be skeptics who question the timeline and the cost, and those doubts are healthy in a democracy. Still, a clear national objective focused on American presence and commercial enablement gives industry and the scientific community something concrete to pursue. Rather than drifting through fragmented programs, a concentrated plan can mobilize talent and capital toward meaningful milestones.

Robotics will play a central role in making a lunar base practical: automated systems can prep sites, mine resources, and assemble habitats before people arrive. Pairing robots with human ingenuity reduces upfront risk and lets crews focus on exploration and scientific gains. If done right, this combination will let the U.S. extend its lead while minimizing some of the most dangerous and costly elements of early settlement.

We should be honest about the work ahead: this is hard, expensive, and technically demanding — but that’s exactly the kind of challenge that builds capability and inspires new generations. The administration’s direction is a call to action for industry, the research community, and policymakers to synchronize efforts. If the U.S. follows through, the next decade could see an American return to the Moon that looks a lot different from Apollo: more permanent, more commercial, and designed to carry us farther into the solar system.

Add comment